House Bill 90 – Education For All: May 2021 Panel Highlights

Before H.B. 90 was passed, children with disabilities were either kept at home or placed in institutions. Back then, the common belief was that people with disabilities could not learn, and children with disabilities were barred from schools. Education for All was the first U.S. law to grant children with disabilities the right to a free and appropriate public education. It was signed into law by Washington State Governor Dan Evans on May 25,1971.

Fifty years later, on May 25, 2021, Northwest Center hosted a virtual panel honoring this landmark civil rights victory. This post contains highlights from the first half of the panel where Northwest Center President & CEO Gene Boes and Northwest Center Chief People Officer Emily Miller talked with Janet Taggart, Bill Dussault, and Senator Dan Evans about their experiences writing, lobbying, and passing Education for All.

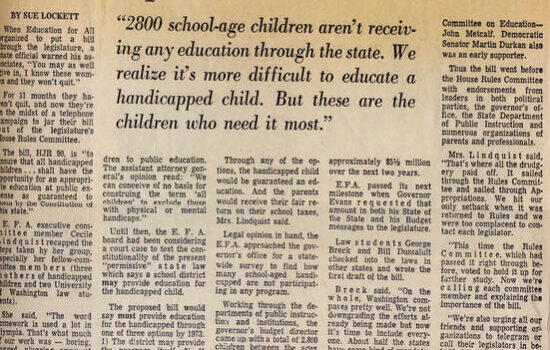

Boes: The legacy of Washington House Bill 90 – Education for All is tied to Northwest Center thanks to our founding mothers: Janet Taggart, who is with us here today, and the late Cecile Lindquist, Evelyn Chapman, and Katie Dolan. These Seattle moms were told that their children didn’t belong in school, the church, or the community, and that they should be put in institutions. And those mothers, rightly so, stood up and said, “Our children can learn, just like every other child.” They started Northwest Center in 1965 and realized quickly that they wanted to help other children. They wrote House Bill 90, which passed in 1971. It became the national blueprint for IDEA (Individuals with Disabilities Education Act), which continues to impact every ZIP code in this country today.

ow, it gives me great pleasure to introduce three people who made history on May 25, 1971.

First, Janet Taggart, one of Northwest Center’s founding mothers, and author of Education for All. Janet and her late husband, Phil, were inspired to work on behalf of children with disabilities by their daughter, Naida, who was barred from attending local schools as a child. Once Janet and the Education for All team got House Bill 90 passed, she went on to help write national disability education legislation. Janet ‘s daughter, Naida, passed away in 2018. But, as you’ll see today, Janet remains just as passionate an advocate for the rights of people of all abilities. And, we’re so grateful to have her here today.

ext, I’d like to introduce Bill Dussault. Bill was a second-year law student at the University of Washington when Northwest Center’s founding mothers recruited him and his classmate to help write a bill that would give all children the right to an education. Now, not only was Bill welcomed for his legal knowledge, he also owned a VW van, and they used that to ferry the team between Seattle and Olympia as they lobbied for their bill to pass. Bill went on to found his own law practice, and has devoted his entire career to disability issues.

Finally, please welcome the Honorable Daniel J. Evans. Dan served three terms as the 16th governor of the state of Washington from 1965 to 1977, and as United States Senator representing Washington state from 1983 to 1989. As governor, Dan founded the country’s first state-level Department of Ecology, which was the blueprint for today’s Federal EPA. He’s a strong supporter of the state’s higher education system. He founded Washington’s system of community colleges. And, from 1977 to 1983, he served as the President of the Evergreen State College in Olympia. Dan has a close connection to Northwest Center. His cousin, Cecile Lindquist, was one of our four founding mothers. She and Dan were cousin to Tommy, a little boy with Down syndrome, who just wanted to go to school like all other kids. Dan advised the Education for All team on how to best shepherd their bill through the Washington state legislature, and he signed the bill into law 50 years ago today.

Okay, now, I’m going to turn the mic over to one of our moderators for today’s panel – Emily Miller. As Chief People Officer, Emily oversees our Human Resources and Recruiting departments, as well as leading our Communications team. Emily is a passionate advocate for diversity, equity, and inclusion, and she founded the Northwest Center Equity Committee in 2015.

Miller: Thank you, Gene.

Janet, it’s quite a pivot to go from being a mom of a beautiful little girl, to founding a school for kids with disabilities, to changing the law for all kids with disabilities. Can you tell us – how did the idea of writing a law first come about?

Taggart: The notion that something had to be done came from many parents who gathered together to form the church basement schools. That, and we had the children who were rejected by the Seattle Public School system. Well, at the beginning of our little basement schools, there were the mothers who were gathering at the little café where we were and complaining about the barriers to education. Some of the barriers were in policies. Often, the obstacle was a person, and we all agreed that the person who personified the rejection of our children was the Director of Special Education for the Seattle Public School system, who had the authority to accept or reject any child’s entry to the system’s programs. Parent supplicants found that visits to his office offered no hope for consideration since no information or document, nor date, was required for entry or rejection. Simply the opinion of this administrator could open or close the door to the public-school education that we were seeking. As a result of that dictatorial method of choosing students for entry, he became the target of loathing, and an identifiable enemy who served as a symbol for parents seeking an education for their children. For good or for bad, that’s what happened. It’s the cohesion of this enemy that brought together the Mother’s Club, and that Mother’s Club became a very effective lobby for the Education for All bills when the time came for us to do that. I think we would classify that as the very beginning of our efforts to pass the law.

Miller: When Education for All passed in 1971, you were in your second year of law school. With your long career focused on disability law, we’d love for you to give us a brief outline of what House Bill 90 covered, and what you can tell us about any major laws or initiatives passed since that time.

Dussault: House Bill 90 was a relatively short bill, only 13 paragraphs long. But, at its foundation, it was a civil rights bill. We wanted to recognize that children who experienced disabilities had a constitutional right to education in the state of Washington. That’s, in fact, where the Education for All name came from – article 9, section 2 of the state constitution. It was the first bill of its kind in the United States requiring that all children – all children, no exception – all had a right to an education; that was one of the foundations of the bill. Secondly, they had a right to an appropriate education, one that was designed around their specific needs. Then, we coupled it with the right of the Superintendent of Public Instruction to sanction school districts who didn’t do it right. It was a transfer of power in the public education system, on a massive level, from educators to parents who knew children best. And, in that regard, it formed the foundation of the disability civil rights movement in the United States.

We’ve always used education as the foundation for our activities in civil rights. Once we had the right to education, we went on to the right for transportation, public housing, employment, access in the community – something as simple as curb cuts – all generated from this law. The entire civil rights movement started with House Bill 90 and moved forward through the Federal Education for All Handicapped Children Act in 1973, title V of the Rehab Act, the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act of 1990, which was the successor to the Education for All Handicapped Children Act and, perhaps most importantly, the Americans with Disabilities Act. All of those flowed from the efforts of these remarkable four women that changed the world for individuals who experience a disability, and they changed it with all modesty, but with incredible tenacity. My hope, now, is that it establishes a floor for what we have, but not a ceiling. We have so much more to do.

Miller: Senator Evans, when your cousin, Cecile, and the Education for All team first approached you about passing a law, what kind of advice did you give them, and what do you remember about that process?

Evans: Well, I remember it pretty vividly because, 50 years ago, we were in a deep recession, and the legislative session was a difficult one. We were just trying to hang on, and I wasn’t terribly interested in starting something new that would get in the way of our survival exercise. But Cecile and Janet and the other two women that joined them were a powerful lobby. There is nothing more powerful than a true citizen’s lobby – people who care deeply about an issue, and who are involved in trying to carry that forward.

So, the first thing that was involved was my education. I wasn’t very much aware of the fact that so many of our young children were being denied an opportunity to even enter the school system. When Cecile and Janet met with me, they asked me what they needed to do. I said, “Well, on an issue like this, you need to educate every single legislator that you can get ahold of because I’m sure that most of them will not be very aware of what you’re trying to do.”

I thought to myself, “Boy, that’s a problem. They’ll never get it done this session. It’ll take several sessions for this to really get in front of the legislature, seriously.” About three days later, I had a report back from Cecile saying, “What do we do next?” I said, “What do you do next?” and she said, “Well, we’ve contacted every legislator.” I thought to myself, “Wow. I need these four women on my permanent legislative team,” because they had done something that I don’t think had ever been done before, and that was to make an intelligent, informed contact with every legislator who was serving. That’s why Education for All was passed during that session. I never thought they had a chance to pass it during the session when we were facing such difficulties with the economy. One of the proudest days of my life was when I sat there with all of them in audience and signed the bill. House Bill 90 was a remarkable piece of legislation made more remarkable because it happened so quickly. But, it was a dramatic step forward nationally, initiated here in the state of Washington, and by a citizen lobby.

Miller: Janet, when Education for All was passed in 1971, where did you think we would be in 2021, and how does that compare to what is really occurring?

Taggart: I expected every child to be able to go to school. I expected that the quality of the programs would improve. I expected to see early learning, early childhood programs, to fit the needs of the children. I considered all of this to be part of today – and it pretty much is. I think I need to remind the people how bad things were originally. Our children were denied not only an education, but they were denied the right to medical insurance coverage. They were denied the right to attend events. Denied the right to go to church. So, things are better now. But, there is still much to do.

I think we have to constantly monitor the legislation that exists. I’d like to see a coordinated parent and professional and advocate organization for children with disabilities, and make them into lobbying entities, based on the model that we used to promote Education for All. I would suggest that we have a single legislative issue to promote annually. I would like to see it advertised and promoted in an annual legislator’s luncheon in each state, where parents and professional people would meet to discuss the issue. I’d like to see a system of communication that would be established that promoted that piece of legislation by a single leader, which would then lead to a series of calls and communication to other advocates, and contact with their state legislators. I’d like to see a system of providing national and organized lobbying to bring about meaningful laws and oversight to provide and protect our children.

I think that the monitoring of our present legislation is very important. And, I think this is important, that we keep in contact with our political leaders – our state and federal political leaders to make a single issue each year, and have it coordinated between all the states, that should be a powerful lobby.

Miller: What is one thing people in our audience could do to help move inclusive education forward?

Dussault: Janet hit on a really key issue, and that is implementation. We’ve got quite a few really wonderful laws on the books over the last 50 years originating out of H.B. 90., but there are no disability policemen. There isn’t anybody out there to make sure this happens, except the people that are directly involved. Individuals who experience disability are wonderful advocates, themselves, and need to be incorporated in this movement, and that leads to real inclusion. We need to move from a parent-organized and -structured advocacy movement, which is critical to continue, to include people who experience disabilities themselves. That brings us to real inclusion.

Evans: I think Janet had one of the absolutely important issues she was talking about, and that is, if you can focus on a single issue and get it really focused on by people and parents and legislators and advocates all across the country, you have built an enormous tidal wave of support, and I think that would be a key element in making continuing progress.

Taggart: I think the most important thing for us to do is to monitor the present legislation, and to stay in touch with our political leaders. We have a big job to do, and a lot of it is in the political field.

Evans: One of the difficulties is that we’re in a time now where we’ve given everyone a megaphone. The single most important advocates the people who care. That’s what drove our success from the very beginning. It was Janet, and her cohorts, and Bill, and a number of citizens who just cared very much- understood there was a real problem, and their biggest job was to educate those of us who really didn’t know as much about the problems that existed, as we probably should have.

But, that still exists. There are lot of people out there who don’t have any feel for what the problems still are for the disabled. We’ve got to have a continuing and growing group of people who, as lobbyists, are absolutely the finest, the best, and the most powerful of any lobbies that appear before the state legislature or the United States Congress.