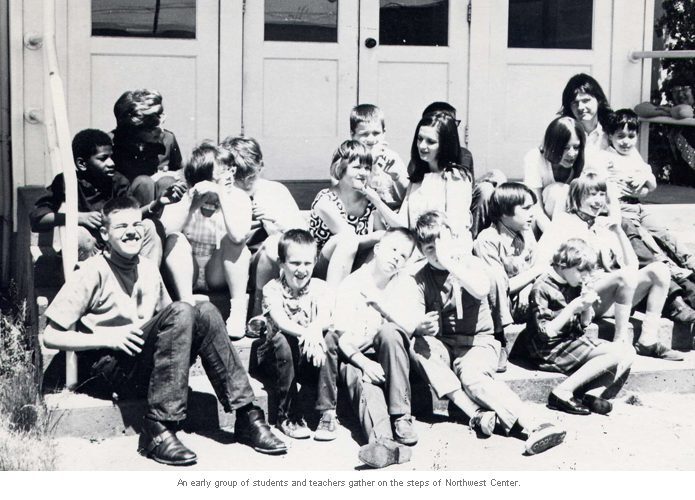

Northwest Center, a school for the children with disabilities who were shut out of public schools in Seattle, had opened two years earlier in 1965. The school’s founders—Cecile Lindquist, Janet Taggart, Evelyn Chapman, and Katie Dolan—were at an event with Ralph Munro (then an assistant to Governor Dan Evans, who would go on to become Secretary of the State of Washington). The women were talking about what to work on next. Munro had a suggestion.

“He said, ‘Why don’t you write a mandatory law that children with disabilities will be served by public schools?’” Lindquist remembers. “‘We thought, ‘Well, there’s an idea for you.’”

Of course, the actual path to that law wasn’t easy, but Northwest Center’s founders were used to hard work. The 80-plus-member Mother’s Guild raised money and awareness with everything from bake sales and bazaars to traveling lectures. Sherry McNary and Mary Bass, who were children at the time, remember the long hours their parents, the late Myrtle and Bob McNary and Nadean and the late Robert Bass, would put in. McNary recalls with amusement how she and her siblings “were always being dragged down there for work parties on nights and weekends. The families did everything.”

“But, boy, that was a good time. Just being with everyone,” Bass says.

Swell Cooks and Super Organizers

But the founders knew that parents who “did everything” was not a long-term solution for the kids with disabilities Northwest Center served, nor for the thousands statewide who still had nowhere to go. Somehow, they had to influence the people who made the laws governing education. A first step was a luncheon for state legislators that the Mother’s Guild cohosted with the Association for Retarded Citizens (now The Arc). Dolan, a well-known local radio and TV personality, invited her friend Fred Dore, who was Chair of the Senate Ways and Means Committee. He was the only lawmaker to show.

Interviewed by Susan Schwartzenberg for the book Becoming Citizens: Family Life and the Politics of Disability (University of Washington Press, 2005), Dolan remembered: “He said to me, ‘Katie, if you want to do this right—you gals are swell cooks and you’re a super organizer…here’s what you should do. It should last one hour, you have every parent call their legislator, and you tell them you’re going to have home-cooked food.”

The following year, Northwest Center followed that advice. Legislators were seated with constituents, there was a clear agenda to cover, and the Legislator’s Luncheons were an instant, long-lasting hit. By the 1980s, remembers board member Parul Houlahan, “We would get phone calls from all the legislators of King County, the city, and the state: ‘I don’t want to miss the Legislator’s Luncheon! When is it?’ Even the bureaucrats would join us.”

They had the ear of the lawmakers; now they needed the law. “Katie Dolan was full of resources,” Chapman says. “She said, ‘Why don’t we go to the University of Washington Law School and see if there are any students to help us out?” Soon, students George Breck and William Dussault were on board, researching current legislation involving people with disabilities.

In Becoming Citizens, Dolan describes the rest of the group as a law-writing dream team:

Evelyn was brilliant; she had experience as a legal secretary and as a budget analyst and could read any law. She was also fearless and would go behind the scenes and talk to anybody. Janet…knew how to connect with people. She was also a journalist. She wrote stories about our progress and fed them to the press. They were delighted; they didn’t have to do any work, and our story got published verbatim. We had Cecile…she had worked with the “establishment.” She knew lobbyists. She was a teacher and an administrator and she was working with the Experimental Education Unit at the University of Washington. We pushed her out front because she had been active politically. I was the dramatist. I was an actress. I had a TV show. I knew how to handle the PR. I knew how to organize events and I had lots of connections.

When the team met with regional legislators and union leaders, they were told it would take years and upwards of $50,000 to pass a law. But then, Chapman says, “We learned to read the Washington State Constitution.” There in the Section 1 Preamble of Article IX was a crucial statement: “It is the paramount duty of the state to make ample provision for the education of all children residing within its borders, without distinction or preference on account of race, color, caste, or sex.”

The newly christened Education for All Team now had their political ammo. They wrote 29 versions of the Education for All Act before they were satisfied. The final law not only mandated that Washington public schools educate all children, but also that schools failing to comply would lose important funding.

The team had a powerful ally in Lindquist’s cousin Dan Evans, who happened to be Governor of Washington. “Cecile and Katie did a good job educating me about developmentally disabled children who shouldn’t be in a state institution or who were prevented from going to school,” Evans remembers. He advised the team to seek out legislators who had children or relatives with developmental disabilities, because the law “would require real change in attitudes.”

‘Nothing slowed them down’

“I told all of them the same thing,” he says: “‘You have to contact and convince legislators—and there are 148 of them.’ Most organizations would say, ‘Oh, that’s impossible.’ Not Cecile and Katie. Nothing slowed them down.”

They also had the Mother’s Guild behind them. “We just had to call one or two mothers, and they would immediately make hundreds of calls to Olympia,” Taggart says. “Legislators would sometimes beg us, ‘Please, turn them off!’” she laughs.

When the bill finally went up for voting in the House of Representatives, “It got stuck in the rules committee,” Lindquist remembers. “One of the legislators did not want there to be sanctions.”

Governor Evans told the team, “‘We’re getting toward the end of the session, and there are 99 members. Contact them all if you can,’” he says. “Then I thought to myself, ‘Well, that’s an impossible task.’ And the next day, they came back and said, ‘Well, we contacted everybody.’”

“And then it went on the floor and it passed,” says Lindquist.

“I was frankly amazed that they could get a bill of that complexity and cost out of the legislature as well and as rapidly as they did,” Evans says.

Gov. Evans signed House Bill (HB) 90, “Education for All,” into law in 1971, flanked by the team who had written and lobbied it into existence. The bill that was supposed to take untold years and $50,000 to get through the legislature had taken just one year and $500.

‘How come nobody ever told me?’

In a very real way, HB 90 led to nationwide change for people with disabilities. First, the team was invited to Washington, D.C. to meet with Senator Warren G. Magnuson.

“We each had our speech, explaining what happened in Washington state, how important it was the whole nation do this,” Lindquist says. “When we finished, there was dead silence in the room.”

Then, Taggart says, the senator suddenly thundered: “Do you mean to tell me there are little boys and girls who can’t go to school?”

“He looked at one of his aides and said, ‘How come nobody ever told me this?’” Lindquist says. “‘We will run a bill this year to change this nationally!’ We were shocked. And the aide is just like, ‘Oh, my God!’ The senator said, ‘There’s no debate. It’s wrong. We will change it.’ And he was a man of his word.”

Members of the team paid their own way to D.C. to help legislators draft the national law inspired by, and named for, their own. The Education for All Handicapped Children Act passed in 1975.

Citizens Who Cared

Big things were also happening at home. In 1967, Northwest Center was approached by William Ellison, who had just opened a thrift store in Renton, WA called Value Village. He proposed a partnership where Northwest Center would collect donated clothing that Value Village would purchase to sell in the store.

Former Northwest Center CEO Jim McClurg recalls, “The finance committee was a bit suspicious—what he was offering sounded too good to be true. But this group of volunteers wasn’t stupid. They invited Bill to make a presentation to the full board, who liked the way it sounded. It was probably one of the most important things we ever decided.”

Today, the partnership is still going strong: Northwest Center collects donations with The Big Blue Truck™ and The Big Blue Bin™ across the state to help fund Early Education and Employment Services.

In 1972, Dolan and Taggart launched family advocacy project The Troubleshooters. They understood the mass of paperwork and government entities families of kids with disabilities had to navigate, so they hosted “benefit parties” to help families fill out forms and published a newsletter with an advice column. Their work was so impressive that Professor Gunnar Dybwad, the leading disability rights advocate at the time, encouraged them to apply for a small scholarship from his wife’s foundation and use it to study disability and family life in Europe. Dolan and Taggart spent time living with families in England, Ireland, Scotland, Czechoslovakia, Denmark, and Sweden.

“Upon our return,” Dolan remembered in 2005, “we wrote and successfully lobbied state legislation, which set up home aid for children with developmental disabilities.”

The Troubleshooters inspired legislation that established Protection and Advocacy agencies in every state. In 1987, The Troubleshooters became the Washington Protection and Advocacy System, an independent entity. Today, it’s known as Disability Rights Washington (DRW).

And of course, Northwest Center programs for children and adults continued to break new ground. Parents worked with the Seattle Parks Department to develop the Specialized Training Program, a clinical approach where students from age 5 to 20 learned appropriate classroom and work behaviors. An on-site workshop known as Special Industries provided training and employment for older students, whose woodwork was sold at craft shows and bazaars. Soon the shop landed the first of many business contracts, making soffits for a local home builder.

By 1975, Northwest Center education and job programs were serving more than 125 people with developmental disabilities, from infants to adults in their 40s.

In just 10 years, the families of Northwest Center accomplished a staggering amount with very little. That’s something that Evans says is an important lesson today. “They demonstrated what citizens who were dedicated to a proposal could really do,” he says. “It didn’t take huge amounts of money. It didn’t take paid lobbyists. It took citizens who cared.”